James Madison, the father of the U.S. Constitution and primary author of the Bill of Rights, repeatedly emphasized that the United States is a “republic” and not a “democracy.” In stark contrast, Jonathan Bernstein, a Bloomberg columnist and former political science professor recently insisted:

- “One of this age’s great crank ideas, that the U.S. is a ‘republic’ and not a ‘democracy’, is gaining so much ground that people in Michigan are trying to rewrite textbooks to get rid of the term ‘democracy’.”

- “For all practical purposes, and in most contexts, ‘republic’ and ‘democracy’ are synonyms.”

- When Madison said that the Constitution established a “republic” and not a “democracy,” he was using a “mild form of propaganda” and “none of this had to do with specific institutions or forms of government. Just word choice.”

Those statements, along with the bulk of Bernstein’s column, are misleading or patently false. In reality:

- People were not trying to remove the term “democracy” from Michigan textbooks. Instead, they proposed education standards that would teach students that the U.S. is a “unique form of democracy.”

- The proposed standards made clear that the U.S. is not merely a “democracy” or a “republic” but a “democratic” and “constitutional republic” that “limits the powers of the federal government.”

- In Madison’s day and now, there are crucial differences between democracies and republics that are vital to the issues of human rights and equal justice.

The Michigan Standards

In 2014, the Michigan Department of Education began to revise its social studies standards, releasing a draft of them in 2018. Soon thereafter, critics began attacking the planned changes as “far-right.” Beyond the issue of whether or not this generalization is cogent, some of the specific allegations used to support it are plainly false.

For example, a Change.org petition signed by more than 75,000 people claims that the standards “would eliminate references to climate change.” In fact, the older standards contain only one reference to climate change, while the newer standards contain two. Notably, these are social studies standards, not environmental science standards.

The article that started the uproar over this issue, which was published by a Michigan news outlet called Bridge, reports that the newer standards “limited” climate change “to an optional example sixth-grade teachers can use when discussing climate in different parts of the planet.” This is deceitful in three respects:

- The newer standards also mention climate change in the context of contemporary global issues.

- The older standards’ lone reference to climate change also appears only in the sixth-grade section of the standards.

- The Michigan Department of Education’s comparison of the older and newer standards states 74 times that the newer standards “relocated” numerous subjects to an “examples column” that spans most of the document. This includes climate change and many other topics, like “Independence Day,” “respect for rule of law,” “taking care of oneself,” “Constitution Day,” and “respect for the rights of others.”

Contrary to what Bridge led its readers to believe, this is not a case of global warming being singled out and relegated to an optional example. This was a general layout change that involved numerous issues, including many conservative ones. Yet instead of correcting Bridge, other media outlets like the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Detroit Free Press repeated these specious allegations.

Likewise, Bernstein’s claim that people were trying to purge the term “democracy” is untrue. The newer standards use the word “democracy” 34 times, including 21 times in the phrase “American Democracy.” In fact, the newer standards actually use the term “democracy” one more time than the older standards.

The newer standards also repeatedly state that the U.S. is a “unique form of democracy” called a “constitutional republic.” This differs from other republics like the People’s Republic of China or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. It also clashes with the agenda of many people in the United States, including some of the nation’s most prominent politicians.

Why It Matters

Bernstein leads his readers to believe that there is no practical difference between republics and democracies. He asserts that “when Madison said the U.S. was a republic and not a democracy, he meant (in today’s vocabulary) that it was a representative democracy, not a direct democracy. Given that all modern democracies employ a ‘scheme of representation,’ that’s an unimportant distinction today.” Bernstein quotes a grand total of five words from one of Madison’s writings to make that case, but the full historical record shows otherwise.

Early during the convention at which the Constitution was written, Madison declared that the government it creates must provide “more effectually for the security of private rights and the steady dispensation of Justice.” He said that violations of these ideals “had more perhaps than any thing else, produced this convention.”

Madison then singled out “democracy” as the cause of those abuses and pointed out that all societies are “divided into different Sects, Factions, and interests,” and “where a majority are united by a common interest or passion, the rights of the minority are in danger.” He stressed that:

- this is “verified by the histories of every country, ancient and modern.”

- this is the cause of slavery, “the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.”

- it is the duty of the convention to “frame a republican system” of government that will better protect the rights of the minority from the will of the majority.

Other delegates to the Constitutional Convention concurred with Madison. Edmund Randolph of Virginia observed “that the general object was to provide a cure for the evils under which the U.S. labored; that in tracing these evils to their origin every man had found it in the turbulence and follies of democracy….” Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts stated: “The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy.”

For the purpose of curbing such evils, Madison and the other framers of the Constitution developed a system of checks and balances on the powers of the government that they formed. In the words of Madison, these provisions were to “guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part” and “will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States.”

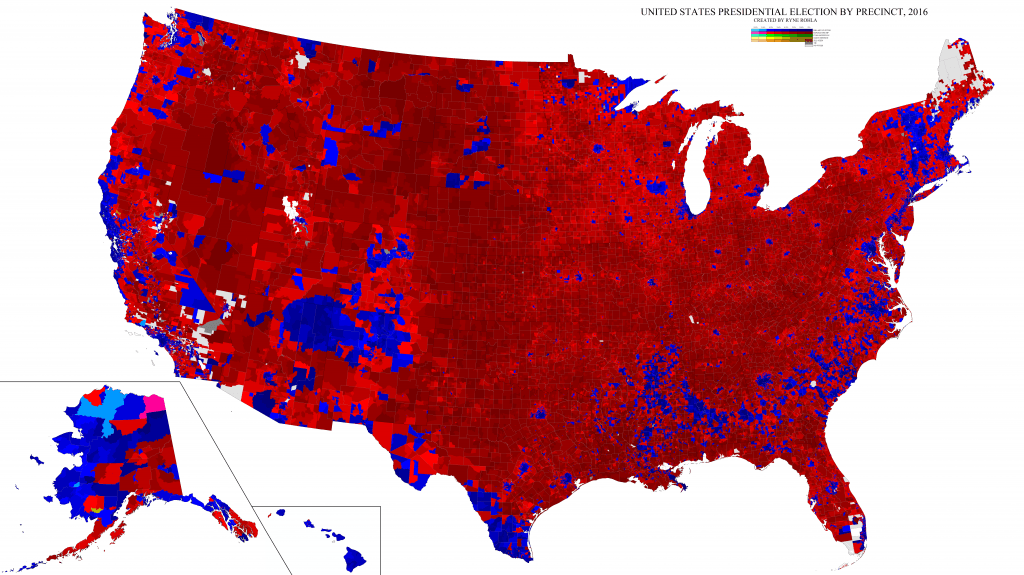

One of these features is the Electoral College, which was designed to prevent highly populated states from dominating the election for U.S. president. As shown below in the electoral precinct map from Washington State University professor Ryne Rohla, the vast majority of America’s communities voted for Donald Trump in 2016. Yet Hillary Clinton’s personal vote count was higher, mainly due to support in big cities:

Exposing the falsity of Bernstein’s storyline, most Democratic presidential hopefuls have called for abolishing the Electoral College based on arguments about democracy. South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg, for example, said of the Electoral College: “It’s gotta go. We need a national popular vote. It would be reassuring from the perspective of believing that we’re a democracy.” Educators build support for such agendas when they teach students that “the U.S. is a democracy” without any qualifiers.

Another major implication is the centralization of power. President Trump and former President Obama have complained about opposition parties standing in the way of their agendas, but the founders created different branches of government for the expressed purpose of “keeping each other in their proper places.” As detailed in Federalist Paper 51, this entails a separation of powers between:

- the states and federal government.

- the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of the federal government.

- the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate.

A mere “representative democracy,” as described by Bernstein, does not necessarily have such features. And without them, a “stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker,” as stated in Federalist 51. Such governments, wrote the paper’s author, are akin to “anarchy,” because “the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger.”

Nonetheless, some people wish the Constitution didn’t have all of these provisions. For instance, Sanford Levinson, a professor of law and government at the University of Texas at Austin has called the Constitution “imbecilic” because its “separation of powers” and “checks and balances” causes “gridlock” that “prevents needed reforms.” He would prefer that the U.S. government had more elements of a “direct democracy.”

All of these facts reveal major differences between the words “democracy” and “republic.” Hence, Bernstein’s blurring of these terms fosters ignorance of the crucial reasons why the founders of the U.S. structured the government as they did.

The Foremost Matter

The most substantial check on unfettered democracy created by the U.S. founders is Article V of the Constitution, which allows it to be amended with the approval of three-quarters of the states. This high bar is meant to stop a simple majority from trampling on the rights of others. At the same time, it gives the Constitution flexibility to change if there is widespread agreement.

Yet, Professor Levinson has argued that the “worst single part of the Constitution” is “surely Article V, which has made our Constitution among the most difficult to amend of any in the world.” He would like to make it easier to change, which would also make it easier for democratically elected majorities to strip people of their constitutional rights. This includes, for example, freedom of speech, the “right to be tried by an impartial jury,” the “right of the people to keep and bear Arms,” and the “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

This is why George Washington, the president of the Constitutional Convention and first U.S. President, highlighted the import of Article V in his farewell address to the nation:

If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed.

Many politicians and jurists have attempted to undercut this restraint on democracy. One of the most candid admissions of this came from Thurgood Marshall, a liberal icon who mentored President Obama’s second Supreme Court appointee, Elena Kagan. When asked to describe his judicial philosophy, Marshall responded, “You do what you think is right and let the law catch up.”

This view is reflected in a third grade social studies textbook titled Our Communities from Macmillan/McGraw-Hill. It states: “The Supreme Court is made up of nine judges. They make sure our laws are fair.”

Marshall’s doctrine—which violates the oath of office that every public official takes to uphold the Constitution—allows a majority of the Supreme Court to flout the Constitution based on their personal notions of right and wrong. Since Supreme Court justices are appointed for life by the president and confirmed by the Senate, these elected officials can effectively void the Constitution by appointing jurists with such mindsets.

That is what occurred in the Supreme Court’s ruling in Korematsu v, United States. In this World War II-era case, six of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s appointees to the Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional for Roosevelt to put U.S. citizens of Japanese descent into detention camps without any evidence that the individuals were disloyal to the United States. These justices ruled in this way in spite of the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment requirement that no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Had the justices faithfully applied the U.S. Constitution in Korematsu, this infringement of human rights would not have happened. However, under democratic standards, it could, and it did.

Conclusion

After the uproar that ensued when the Michigan Board of Education released draft social studies standards in May of 2018, an election changed the composition of the board from an equal number of Republicans and Democrats to two Republicans and six Democrats. This new board released an altered draft of the standards in March of 2019.

These latest standards never use the phrase “constitutional republic,” which appeared 43 times in the previous standards. Instead, they use similar phrases among a jumble of other terms to describe the U.S. government, such as “republican government,” “constitutional government,” “American democracy,” “representative republic,” and “Constitutional Democracy.”

To Madison and other framers of the Constitution, the words “democracy” and “republic” had important differences. Democracy meant majority rule, and it still has this connotation today. A republic, on the other hand, meant a democratic government with limited powers that are widely divided among different voting blocs in order to protect the rights of as many people as possible.

Towards that end, the founders of the U.S. produced what is now the longest-standing constitution of all nations in the world. As explained by Encyclopædia Britannica, it is “the oldest written national constitution in use,” and it “has served as a model for other countries, its provisions being widely imitated in national constitutions throughout the world.”

Like many words, the meanings of “democracy” and “republic” have changed over past centuries, and neither now fully describes the United States or differentiates it from other “republics” like the People’s Republic of China. A term that arguably does that is “democratic constitutional republic.” This captures in modern terminology the key elements that the founders put in place.

The U.S. also distinguishes itself from other democratic constitutional republics by virtue of its stronger protections against tyranny by majorities. However, the practical application of this is sometimes undercut by politicians and jurists who violate their oaths of office and place their personal agendas over that of the Constitution.

--

This article was republished with permission from Just Facts Daily.

[Image Credit: U.S. Air Force]

via IFTTT