Authored by Ruchir Sharma, op-ed via The New York Times,

The policies created to pull the world out of recession are still in place, but now they are strangling the global economy...

The United States’ recovery from the Great Recession recently turned 10 years old, matching the longest American expansion since records were first kept in the 1850s. The global recovery will also turn 10, in January, if it lasts that long — and that, too, would be a record.

But there have been few celebrations, in part because trade tensions have further slowed the pace of recovery. Since the end of the recession, the economy has grown at about 2 percent a year in the United States and 3 percent worldwide - both nearly a point below the average for postwar recoveries.

What explains the longest, weakest recovery on record? I blame the unintended consequences of huge government rescue programs, which have continued since the recession ended.

Before 2008, more open trade borders and better internet communications promoted strong growth by leveling the playing field, inspiring the Times columnist Thomas Friedman to declare that “the world is flat.”

Once the crisis hit, however, governments erected barriers to protect domestic companies. Central banks aggressively printed money to restore high growth. Instead, growth came back in a sluggish new form, as easy money propped up inefficient companies and gave big companies favorable access to cheap credit, encouraging them to grow even bigger.

If the world was flat and fast before 2008, today it’s fat and slow.

Central bankers had hoped that low interest rates would spur investment, increasing productivity and boosting growth. But a recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that low rates gave big companies an incentive and means to grow bigger. As their power grows, workers’ share of national income has been shrinking, fueling inequality — and anger.

Four airlines and three rental car companies account for more than 80 percent of the American travel markets. Go into any American mall and you can buy jewelry at Zales, Jared, Kay and several other chains, all now owned by the same parent company. These days tech insurgents aspire to be purchased by Google and Facebook, not to replace them.

As big companies grow more dominant, life gets tougher for entrepreneurs. Start-ups represent a declining share of all companies in Britain, Italy, Spain, Sweden, the United States and many other industrialized economies. The United States is generating start-ups — and shutting down established companies — at the slowest rates since at least the 1970s.

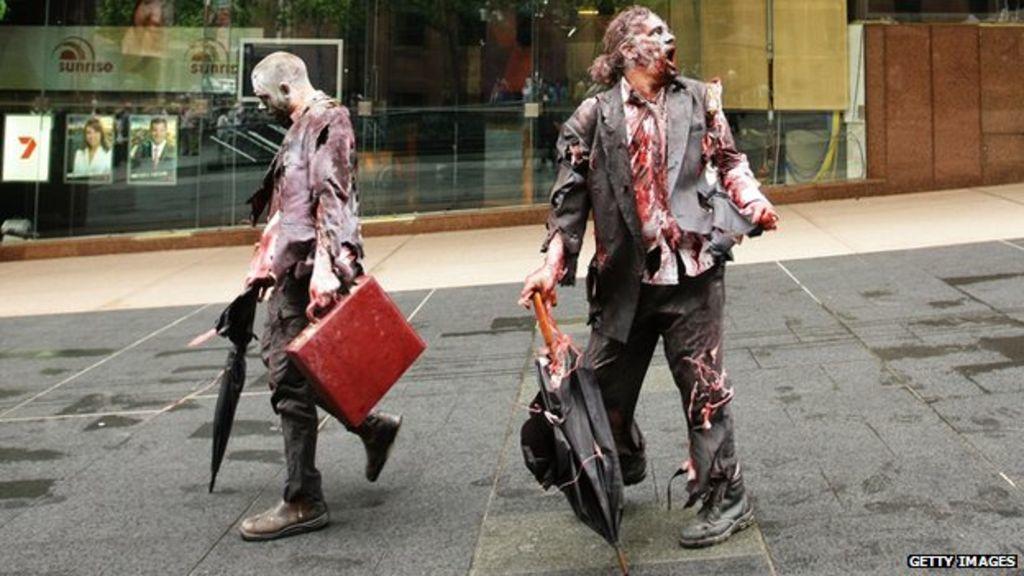

The Bank for International Settlements, the global bank that serves central banks, says low rates are fueling the rise of “zombie firms,” which don’t earn enough profit to cover their interest payments and survive by repeatedly refinancing their loans.

Zombies now account for 12 percent of the companies listed on stock exchanges in advanced economies and 16 percent in the United States, up from 2 percent in the 1980s. Companies are surviving in the “zombie state” for longer, depleting the productivity of healthy companies by competing with them for capital, materials and labor.

These, then, are the trademarks of the fat and slow world: larger corporations, declining competition and fewer start-ups, which together undermine and slow economies already hindered by falling growth in the working-age population.

The bright side of endless stimulus, if there is one, is that recessions have become increasingly rare. Only 7 percent of the nearly 200 countries tracked by the International Monetary Fund suffered negative growth last year; that is about half the average share since records began. The I.M.F. projects that share will fall to 3 percent in 2020, close to a record low.

A global economy ruled by big, indebted companies looks sluggish but, in the view of many commentators, also very stable. Even as trade wars undermine economic growth, most investors assume central banks will ride to the rescue before it deteriorates into outright recession.

The problem, however, is that government stimulus programs were conceived as a way to revive economies in recession, not to keep growth alive indefinitely. A world without recessions may sound like progress, but recessions can be like forest fires, purging the economy of dead brush so that new shoots can grow. Lately, the cycle of regeneration has been suspended, as governments douse the first flicker of a coming recession with buckets of easy money and new spending. Now experiments in permanent stimulus are sapping the process of creative destruction at the heart of any capitalist system and breeding oversize zombies faster than start-ups.

To assume that central banks can hold the next recession at bay indefinitely represents a dangerous complacency. Corporate debt levels continue to rise; government debts and deficits continue to rise. If there is a sudden break in confidence, the damage will be that much greater and governments may find themselves too broke to stem it.

Until then, we are in a fat and slow world.

* * *

Ruchir Sharma, author of “The Rise and Fall of Nations: Forces of Change in the Post-Crisis World,” is the chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management and a contributing opinion writer.

via IFTTT

InoreaderURL: SECONDARY LINK