https://www.theatlantic.com/newsletters/editor-in-chief-newsletter/

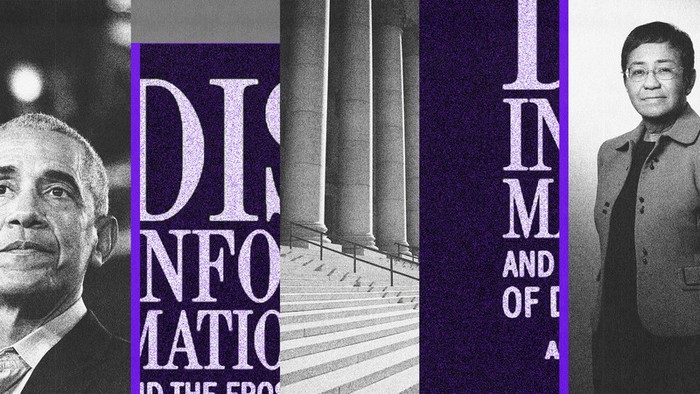

On Disinformation

Last week, a Michigan congresswoman whose existence had not yet entered the rest of the country’s consciousness credited Donald Trump with having “caught Osama bin Laden,” among other terrorists. It is difficult to forget that night in 2011 when Barack Obama told the world that, on his orders, a team of Navy commandos had killed the al-Qaeda leader. But Representative Lisa McClain, a first-term member of Congress, showed that, with effort, and with a desire to feed Trump’s delusions and maintain her standing among his supporters, anything is possible. In ordinary times, McClain’s claim would have been mocked and then forgotten. But because these are not ordinary times—these are times in which citizens of the same country live in entirely different information realities—I put her assertion about bin Laden on a kind of watch list. In six months, I worry, we may learn that a provably false claim made by a single unserious congressional backbencher has spread into MAGA America, a place where Barack Obama is believed to be a Kenyan-born Muslim and Donald Trump is thought to be the victim of a coup. Disinformation is the story of our age. We see it at work in Russia, whose citizens have been led to believe the lies that Ukraine is an aggressor nation and that the Russian army is winning a war against modern-day Nazis. We see it at work in Europe and the Middle East, where conspiracies about hidden hands and occult forces are adopted by those who, in the words of the historian Walter Russell Mead, lack the ability to “see the world clearly and discern cause and effect relations in complex social settings.” We see it weaponized by authoritarians around the globe, for whom democracy, accountability, and transparency pose mortal threats. And we see it, of course, in our own country, in which tens of millions of voters believe that Joe Biden is an illegitimate president because the man he beat in 2020 specializes in sabotaging reality for personal and political gain. This mass delusion has enormous consequences for the future of democracy. As my colleague Yoni Appelbaum has noted, “Democracy depends on the consent of the losers.” Sophisticated, richly funded, technology-enabled disinformation campaigns are providing losers with other options. The threat posed by disinformation is the reason The Atlantic is joining with the Institute of Politics at the University of Chicago to stage a conference, starting today, that is meant to examine disinformation in all of its manifestations. When David Axelrod, the founder and leader of the IOP, and I first discussed this idea, we both agreed that the future of this country—and of our democratic allies around the world—depends on the ability and willingness of citizens to discern truth from falsehood. “It is a fundamental blow to our democracy—and any democracy—if people come to believe that an election clearly won by one person was illegitimate,” Axelrod told me. “That kind of malign fabrication is devastating for democracy. Anything that tears us apart, falsehoods that deepen distrust of institutions, anything that undermines the idea that there is such a thing as objective truth—these are huge challenges.” Axelrod and I are both aware that disinformation is a virus that has infected much more than a single political party (though in my opinion, only one party in the American system has currently given itself over so comprehensively to fantasists). And we’re aware that there is only so much any citizen can do, when faced with a social media–Big Data complex that makes it easier and easier to inject falsehoods into political discourse. “Disinformation, turbocharged by the tools social media and Big Data now afford, threatens to unravel not just our democracy but democracies everywhere,” he said. Any conference about disinformation will have some fraught qualities, starting with basic definitions. What is the difference between disinformation and misinformation? What is the difference between disinformation and information you simply don’t like, or find narratively inconvenient? These are answerable questions, but the answers contain a great degree of nuance in a rapidly shifting informational environment. This is a particularly challenging subject for journalists, and for someone like Axelrod, Obama’s former chief strategist (and a former journalist himself). “There’s no doubt that I, like everyone, took facts and arranged them in a way that would be most persuasive to the audience we were trying to win,” he said. “But that’s fundamentally different than creating stories that are wholly untrue and designed to polarize factions and achieve authoritarian goals. The lie about the Obama birth certificate, the Pizzagate conspiracy—these are examples of what we’re talking about.” Disinformation is also a fraught subject for a big-tent magazine like ours, one that believes it is best for democracy to offer a wide variety of views and opinions. We strive for nonpartisanship at The Atlantic, and we aim to publish independent thinkers and a wide variety of viewpoints. But this most recent period in American history has presented what might be called “both-sides journalism” with serious challenges—challenges that have prevented this magazine from publishing many pro-Trump articles. (After all, our articles must pass through a rigorous fact-checking process.) |