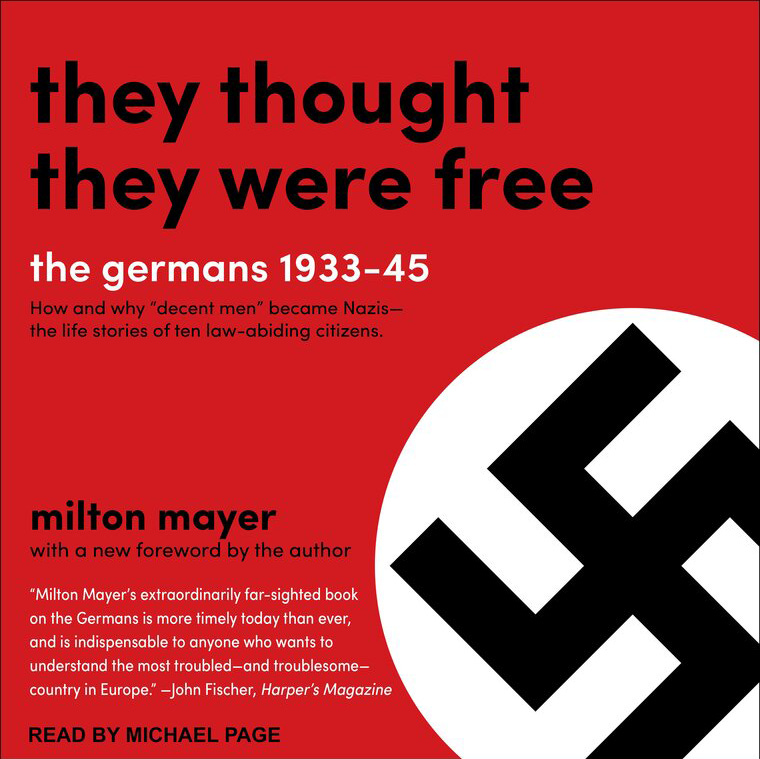

My dad bought this book when I was in grade school. I finally read/skimmed it in my senior year of high school. My recollection is that it was a damned good read although, frankly, I don’t recall most of it. I’m going to have to read it again. I copied the following quote as well as the contents of this article from Margaret Anna Alice’s website. She summarizes the book;

” ….. 1956 National Book Award finalist featuring interviews with 10 German Nazis while the experience was still fresh in their minds. Mayer’s discovery is these weren’t evil men; rather, they were indistinguishable from Americans or anyone else. His aim was to understand how these average Germans could succumb to such a savage ideology.”

America is marching towards a dictatorship / totalitarianism. Already people are wondering how this happened. Many more will be asking that in the coming years. Well, reading how it happened in 1930’s Germany will answer a lot of questions. The comparisons to America today are uncanny. The implications are terrifying. History really is repeating itself. Only one question remains; can we reverse course or, are we doomed to drive off the cliff?

===

Crisis is our diet, served up as exotic dishes and dishes ever more exotic before we are able to swallow, let alone digest, those that were just before us.

===

That Nazism in Germany meant mistrust, suspicion, dread, defamation, and destruction we learned from those who brought us word of it—from its victims and opponents whose world was outside the Nazi community and from journalists and intellectuals, themselves non-Nazi or anti-Nazi, whose sympathies naturally lay with the victims and opponents.… those who did not dissent or associate with dissenters saw no mistrust or suspicion beyond the great community’s mistrust and suspicion of dissenters, while those who dissented or believed in the right to dissent saw nothing but mistrust and suspicion and felt its devastation.… there were two Germanys.

===

None of these nine ordinary Germans … thought then or thinks now that the rights of man, in his own case, were violated or even more than mildly inhibited for reasons of what they then accepted (and still accept) as the national emergency proclaimed four weeks after Hitler took office as Chancellor.

===

Men who are going to protest or take even stronger forms of action, in a dictatorship more so than in a democracy, want to be sure. When they are sure, they still may not take any form of action (in my ten friends’ cases, they would not have, I think); but that is another point. What you hear of individual instances, second- or thirdhand, what you guess as to general conditions, having put half-a-dozen instances together, what someone tells you he believes is the case—these may, all together, be convincing. You may be ‘morally certain,’ satisfied in your own mind. But moral certainty and mental satisfaction are less than binding knowledge. What you and your neighbors don’t expect you to know, your neighbors do not expect you to act on, in matters of this sort, and neither do you.

===

‘Oh, things seeped through somehow, always quietly, always indirectly. So people heard rumors, and the rest they could guess. Of course, most people did not believe the stories of Jews or other opponents of the regime. It was naturally thought that such persons would all exaggerate.’

===

Rumors, guesses enough to make a man know if he wanted badly to know, or at least to believe, and always involving persons who would be suspected, ‘naturally,’ of exaggerating. Goebbels’ immediate subordinate in charge of radio in the Propaganda Ministry testified at Nuremberg that he had heard of the gassing of Jews, and went to Goebbels with the report. Goebbels said it was false, ‘enemy propaganda,’ and that was the end of it.”

===

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, with its fantastically rapid development of a central record of an ever increasing number of Americans, law-abiding and lawless, is something new in America. But it is very old in Germany, and it had nothing to do with National Socialism except to make it easier for the Nazi government to locate and trace the whole life-history of any and every German. The German system—it has its counterpart in other European countries, including France—was, being German, extraordinarily efficient.

===

He asked me whether I had known anybody connected with the West Coast deportation. When I said ‘No,’ he asked me what I had done about it. When I said ‘Nothing,’ he said, triumphantly, ‘There. You learned about all these things openly, through your government and your press. We did not learn through ours. As in your case, nothing was required of us—in our case, not even knowledge. You knew about things you thought were wrong—you did think it was wrong, didn’t you, Herr Professor?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘So. You did nothing. We heard, or guessed, and we did nothing. So it is everywhere.’ When I protested that the Japanese-descended Americans had not been treated like the Jews, he said, ‘And if they had been—what then? Do you not see that the idea of doing something or doing nothing is in either case the same?’

===

A few hundred at the top, to plan and direct at every level; a few thousand to supervise and control (without a voice in policy) at every level; a few score thousand specialists (teachers, lawyers, journalists, scientists, artists, actors, athletes, and social workers) eager to serve or at least unwilling to pass up a job or to revolt; a million of the Pöbel, which sounds like ‘people’ and means ‘riffraff,’ to do what we would call the dirty work, ranging from murder, torture, robbery, and arson to the effort which probably employed more Germans in inhumanity than any other in Nazi history, the standing of ‘sentry’ in front of Jewish shops and offices in the boycott of April, 1933.

===

I was nothing. Then, suddenly, I was needed. National Socialism had a place for me. I was nothing—and then I was needed.

The propaganda didn’t make me think of him as I knew him but of him as a Jew.

===

What happened here was the gradual habituation of the people, little by little, to being governed by surprise; to receiving decisions deliberated in secret; to believing that the situation was so complicated that the government had to act on information which the people could not understand, or so dangerous that, even if the people could understand it, it could not be released because of national security. And their sense of identification with Hitler, their trust in him, made it easier to widen this gap and reassured those who would otherwise have worried about it.

This separation of government from people, this widening of the gap, took place so gradually and so insensibly, each step disguised (perhaps not even intentionally) as a temporary emergency measure or associated with true patriotic allegiance or with real social purposes. And all the crises and reforms (real reforms, too) so occupied the people that they did not see the slow motion underneath, of the whole process of government growing remoter and remoter.

===

The dictatorship, and the whole process of its coming into being, was above all diverting. It provided an excuse not to think for people who did not want to think anyway.… Most of us did not want to think about fundamental things and never had. There was no need to. Nazism gave us some dreadful, fundamental things to think about—we were decent people—and kept us so busy with continuous changes and ‘crises’ and so fascinated, yes, fascinated, by the machinations of the ‘national enemies,’ without and within, that we had no time to think about these dreadful things that were growing, little by little, all around us. Unconsciously, I suppose, we were grateful. Who wants to think?

Too live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it—please try to believe me—unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness, acuity, than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, unless one understood what the whole thing was in principle, what all these ‘little measures’ that no ‘patriotic German’ could resent must some day lead to, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.

How is this to be avoided, among ordinary men, even highly educated ordinary men? Frankly, I do not know. I do not see, even now. Many, many times since it all happened I have pondered that pair of great maxims, Principiis obsta and Finem respice—‘Resist the beginnings’ and ‘Consider the end.’ But one must foresee the end in order to resist, or even see, the beginnings. One must foresee the end clearly and certainly and how is this to be done, by ordinary men or even by extraordinary men? Things might have changed here before they went as far as they did; they didn’t, but they might have. And everyone counts on that might.

===

One doesn’t see exactly where or how to move. Believe me, this is true. Each act, each occasion, is worse than the last, but only a little worse. You wait for the next and the next. You wait for one great shocking occasion, thinking that others, when such a shock comes, will join with you in resisting somehow. You don’t want to act, or even talk, alone; you don’t want to “go out of your way to make trouble.” Why not?—Well, you are not in the habit of doing it. And it is not just fear, fear of standing alone, that restrains you; it is also genuine uncertainty.

Uncertainty is a very important factor, and, instead of decreasing as time goes on, it grows. Outside, in the streets, in the general community, “everyone” is happy. One hears no protest, and certainly sees none.” … In the university community, in your own community, you speak privately to your colleagues, some of whom certainly feel as you do; but what do they say? They say, “It’s not so bad” or “You’re seeing things” or “You’re an alarmist.”

And you are an alarmist. You are saying that this must lead to this, and you can’t prove it. These are the beginnings, yes; but how do you know for sure when you don’t know the end, and how do you know, or even surmise, the end? On the one hand, your enemies, the law, the regime, the Party, intimidate you. On the other, your colleagues pooh-pooh you as pessimistic or even neurotic. You are left with your close friends, who are, naturally, people who have always thought as you have.

===

But the one great shocking occasion, when tens or hundreds or thousands will join with you, never comes. That’s the difficulty. If the last and worst act of the whole regime had come immediately after the first and smallest, thousands, yes, millions would have been sufficiently shocked—if, let us say, the gassing of the Jews in ’43 had come immediately after the “German Firm” stickers on the windows of non-Jewish shops in ’33. But of course this isn’t the way it happens. In between come all the hundreds of little steps, some of them imperceptible, each of them preparing you not to be shocked by the next. Step C is not so much worse than Step B, and, if you did not make a stand at Step B, why should you at Step C? And so on to Step D.

And one day, too late, your principles, if you were ever sensible of them, all rush in upon you. The burden of self-deception has grown too heavy, and some minor incident, in my case my little boy, hardly more than a baby, saying “Jew swine,” collapses it all at once, and you see that everything, everything, has changed and changed completely under your nose. The world you live in—your nation, your people—is not the world you were born in at all. The forms are all there, all untouched, all reassuring, the houses, the shops, the jobs, the mealtimes, the visits, the concerts, the cinema, the holidays. But the spirit, which you never noticed because you made the lifelong mistake of identifying it with the forms, is changed. Now you live in a world of hate and fear, and the people who hate and fear do not even know it themselves; when everyone is transformed, no one is transformed. Now you live in a system which rules without responsibility even to God. The system itself could not have intended this in the beginning, but in order to sustain itself it was compelled to go all the way.

You have gone almost all the way yourself. Life is a continuing process, a flow, not a succession of acts and events at all. It has flowed to a new level, carrying you with it, without any effort on your part. On this new level you live, you have been living more comfortably every day, with new morals, new principles.

You have accepted things you would not have accepted five years ago, a year ago, things that your father, even in Germany, could not have imagined.

Suddenly it all comes down, all at once. You see what you are, what you have done, or, more accurately, what you haven’t done (for that was all that was required of most of us: that we do nothing). You remember those early meetings of your department in the university when, if one had stood, others would have stood, perhaps, but no one stood. A small matter, a matter of hiring this man or that, and you hired this one rather than that. You remember everything now, and your heart breaks. Too late. You are compromised beyond repair.

===

I was employed in a defense plant (a war plant, of course, but they were always called defense plants). That was the year of the National Defense Law, the law of “total conscription.” Under the law I was required to take the oath of fidelity. I said I would not; I opposed it in conscience. I was given twenty-four hours to “think it over.” In those twenty-four hours I lost the world.… “What I tried to think of was the people to whom I might be of some help later on, if things got worse (as I believed they would). I had a wide friendship in scientific and academic circles, including many Jews, and ‘Aryans,’ too, who might be in trouble. If I took the oath and held my job, I might be of help, somehow, as things went on. If I refused to take the oath, I would certainly be useless to my friends, even if I remained in the country. I myself would be in their situation.

The next day, after “thinking it over,” I said I would take the oath with the mental reservation that, by the words with which the oath began, “Ich schwöre bei Gott, I swear by God,” I understood that no human being and no government had the right to override my conscience. My mental reservations did not interest the official who administered the oath. He said, “Do you take the oath?” and I took it. That day the world was lost, and it was I who lost it.”

‘Do I understand,’ I said, ‘that you think that you should not have taken the oath?’

‘Yes.’

‘But,’ I said, ‘you did save many lives later on. You were of greater use to your friends than you ever dreamed you might be.’…

‘First of all, there is the problem of the lesser evil. Taking the oath was not so evil as being unable to help my friends later on would have been. But the evil of the oath was certain and immediate, and the helping of my friends was in the future and therefore uncertain. I had to commit a positive evil, there and then, in the hope of a possible good later on. The good outweighed the evil; but the good was only a hope, the evil a fact.’

‘But,’ I said, ‘the hope was realized. You were able to help your friends.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but you must concede that the hope might not have been realized—either for reasons beyond my control or because I became afraid later on or even because I was afraid all the time and was simply fooling myself when I took the oath in the first place.’…

‘If I had refused to take the oath in 1935, it would have meant that thousands and thousands like me, all over Germany, were refusing to take it. Their refusal would have heartened millions. Thus the regime would have been overthrown, or, indeed, would never have come to power in the first place. The fact that I was not prepared to resist, in 1935, meant that all the thousands, hundreds of thousands, like me in Germany were also unprepared, and each one of these hundreds of thousands was, like me, a man of great influence or of great potential influence. Thus the world was lost.’…

‘My education did not help me,’ he said, ‘and I had a broader and better education than most men have had or ever will have. All it did, in the end, was to enable me to rationalize my failure of faith more easily than I might have done if I had been ignorant. And so it was, I think, among educated men generally, in that time in Germany. Their resistance was no greater than other men’s.’

===

My ten friends had been told, not since 1939 but since 1933, that their nation was fighting for its life. They believed that self-preservation is the first law of nature, of the nature of nations as well as of herd brutes. Were they wrong in this principle? If they were, they saw nothing in the history of nations (their own or any other) that said so. And, once there was shooting war, their situation was like that of the secret opponents of the regime whom my colleague described: there was no further need for the nation, or anyone in it, to be justified. The nation was literally fighting for its literal life—‘they or we.’ Anything went, and what ‘anything’ was, what enormities it embraced, depended entirely on the turn of the battle.

===

You see, the young people, and, yes, the old, too, were drawn to opposite extremes in those years. People outside Germany seem to think that ‘the Germans’ came to believe everything they were told, all the dreadful nonsense that passed for truth. It is a very bad mistake, a very dangerous mistake, to think this. The fact, I think, is that most Germans came to believe everything, absolutely everything; but the rest, those who saw through the nonsense, came to believe nothing, absolutely nothing. These last, the best, are the cynics now, young and old.

===

Everything was not regulated specifically, ever. It was not like that at all. Choices were left to the teacher’s discretion, within the ‘German spirit.’ That was all that was necessary; the teacher had only to be discreet. If he himself wondered at all whether anyone would object to a given book, he would be wise not to use it. This was a much more powerful form of intimidation, you see, than any fixed list of acceptable or unacceptable writings. The way it was done was, from the point of view of the regime, remarkably clever and effective. The teacher had to make the choices and risk the consequences; this made him all the more cautious.

===

When were you really disillusioned with National Socialism?” I said in a later conversation.

The blush again; deeper, this time. “Only after the war—really.”

“That discourages me,” I said, “because you are so much more sensitive than most people, and this makes me realize how hard it must be, under such conditions, for people, even sensitive people, to see what is going on around them.” He continued to blush, but my blush-detector told me that this was not it.

“It’s all so well masqueraded,” he said, “the bad always mixed up with the good and the harmless, and you tell yourself that you are making up for the bad by doing a few little things like speaking of Mendelssohn in class.

===

Take Germany as a city cut off from the outside world by flood or fire advancing from every direction. The mayor proclaims martial law, suspending council debate. He mobilizes the populace, assigning each section its tasks. Half the citizens are at once engaged directly in the public business. Every private act—a telephone call, the use of an electric light, the service of a physician—becomes a public act. Every private right—to take a walk, to attend a meeting, to operate a printing press—becomes a public right. Every private institution—the hospital, the church, the club—becomes a public institution. Here, although we never think to call it by any name but pressure of necessity, we have the whole formula of totalitarianism.

The individual surrenders his individuality without a murmur, without, indeed, a second thought—and not just his individual hobbies and tastes, but his individual occupation, his individual family concerns, his individual needs. The primordial community, the tribe, re-emerges, its preservation the first function of all its members. Every normal personality of the day before becomes an ‘authoritarian personality.’ A few recalcitrants have to be disciplined (vigorously, under the circumstances) for neglect or betrayal of their duty. A few groups have to be watched or, if necessary, taken in hand—the antisocial elements, the liberty-howlers, the agitators among the poor, and the known criminal gangs. For the rest of the citizens—95 per cent or so of the population—duty is now the central fact of life. They obey, at first awkwardly but, surprisingly soon, spontaneously.

The community is suddenly an organism, a single body and a single soul, consuming its members for its own purposes. For the duration of the emergency the city does not exist for the citizen but the citizen for the city.

===

Substances move, under pressure, to extreme positions and, when they shift positions, shift from one extreme to the other. Men under pressure are drained of their shadings of spirit, of their sympathy (which they can no more give than get), of their serenity, their sweetness, their simplicity, and their subtlety. Their reactions are structuralized; like rubber balls (which we say have “life” in them because they react in such lively fashion to the living impulse outside them), the harder they are bounced, the higher they go. Such men, when they are told not to cut down a tree, won’t cut down a tree, but when they are not told not to cut down a man, they may cut down a man.

===

Men under pressure are first dehumanized and only then demoralized, not the other way around. Organization and specialization, system, subsystem, and supersystem are the consequence, not the cause, of the totalitarian spirit. National Socialism did not make men unfree; unfreedom made men National Socialists.

Freedom is nothing but the habit of choice. Now choice is remarkably wide in this life. Each day begins with the choice of tying one’s left or right shoelace first, and ends with the choice of observing or ignoring the providence of God. Pressure narrows choice forcibly. Under light pressure men sacrifice small choices lightly. But it is only under the greatest pressure that they sacrifice the greatest choices, because choice, and choice alone, informs them that they are men and not machines.

The ultimate factor in choosing is common sense, and it is common sense that men under pressure lose fastest, cut off as they are (in besieged ‘Peoria’) from the common condition. The harder they are pressed, the harder they reason; the harder they must reason. But they tend to become unreasonable men; for reasonableness is reason in the world, and ‘Peoria’ is out of this world.

===

Freedom is risky business; when I let my little boy cross the street alone for the first time, I am letting him risk his life, but unless I do he will grow up unable to cross the street alone.… But it was the fear of freedom, with all its dangers, that got the Germans into trouble in the first place.…

Free inquiry on a free platform is the only practice that distinguishes a free from a slave society.

THE END

via IFTTT

InoreaderURL: SECONDARY LINK